From the

ARCHITECTURAL REVIEW

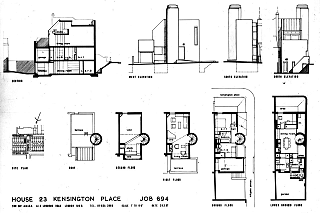

The house stands on a corner site replacing a small Victorian terrace house in Kensington Place. It is entered from Hillgate Street by means of a diagonal ramp up to the ground floor or down an external stair through the kitchen garden. It is directly opposite a primary school and bounded by narrow streets, and the problem of gaining privacy and good natural lighting led to the decision to put the double-height living room at first floor level.

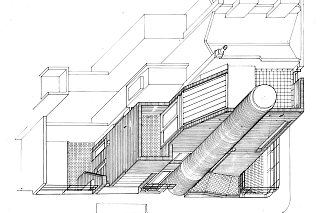

The roof of the garage serves as a walled terrace leading out of the living room. Another terrace on the main roof is reached from the top flight of an internal spiral staircase. This staircase was pushed out beyond the building line to gain planning freedom and additional floor space.

The brick and timber structure is stiffened by reinforced concrete slab at first floor level. As in the demolished house, the party wall carries only the roof. The floors are supported on piers via trimmers parallel to the party wall, except the gallery which

bears directly on to the piers.

The bricks are Staffordshire Blues used fairface internally in the living room and on the staircase. Partitions are faced with beech ply except in the bathroom which is tiled. Ceilings are plastered. The lower ground floor slab and the kitchen walls are clad in blue-black quarry tiles . The built-in light fittings, storage unit supports and the spiral staircase are all precast concrete. The staircase handrails are polythene water piping. A hoist serves all floors except the gallery.

From HOUSE & GARDEN

Christopher Bailey, one of London’s leading commercial photographers, and his opera-singer wife, Angela Hickey, bought a small corner house in Kensington Place, one of those mid-Victorian dolls-house streets in that charming complex of terraces, squares and culs-de-sac which lie between Church Street and Holland Park.

They had definite ideas about the number of rooms they wanted and so on, and commissioned Tom Kay, ARIBA, to produce plans for converting and extending the existing house to make a modern labour-saving home. When the architect drew up the plans it be came obvious that the alterations would have to be extensive and the quantity surveyor’s report showed that they would be costly to effect-something like two-thirds, in fact, of the cost of a new building.

The Baileys thereupon made the courageous decision not only to build, but to build the absolutely bang-up-to-the-minute kind of house they had hitherto merely talked about as a possibility a decade or so hence. They asked Tom Kay to prepare plans for a new house. In any commission of this kind, it is essential that the client should give the architect a good brief, one that is as detailed as possible, at the same time allowing the designer maximum freedom for his skills and imagination. In this way, the Baileys were ideal clients throughout the entire operation. Even the briefs for furniture and fittings were detailed enough for the architect to work from.

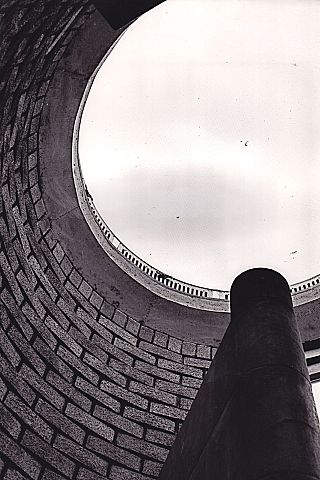

Tom Kay’s first scheme included a spiral staircase inside the house, but, in view of the many differing activities of the family, this would have proved a space-waster of substantial proportions, so he decided to build the spiral outside the building. The idea alone was odd enough in a context of small up-and-down Victorian terrace houses, but they did have a corner site and they could start from scratch. The evolution of the idea was stranger still, for the architect set about evolving a plan based on a staircase within a well of six-feet diameter.

Yet, even so, in order to push the staircase out to give the Baileys adequate room, official permission had to be sought and obtained. This not only added to the net available floor area (1,900 square feet in toto) but, more importantly, increased the flexibility of the internal planning on the narrow site-13 feet 6 inches from building line to party wall! It also enabled the design of the living-room to extend from front to back of the house without obstruction and extend on to a roof terrace.

All in all, the staircase, concentrated in towered, offered the only practical plan which would not occupy too much space outside the building line and would start and end logically and correctly, at landings.

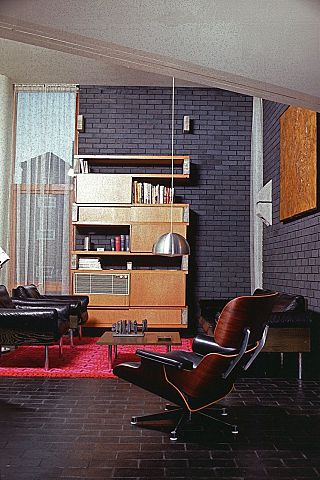

The architect had to work out in detail a plan that would satisfy the domestic requirements of husband and wife with their divergent careers and recreations. The major requirements was a large living-room, and this the Baileys have undoubtedly got: a large room of unusual shape approaching nearly 30 feet long and 13 feet wide, occupying the whole plan area, with two pleasantly varied ceiling levels which were necessary in order to accommodate the most novel-and logical-element in this room: a gallery which cuts across the room and adds enormously to the visual excitement of the room. Opening out of this room is a roof terrace of ample size, an unusual amenity in London, and a sun-trap throughout pleasant afternoons.The most dramatic aspect of the house, externally and internally derives from the use of the fairfaced dark blue-grey engineering brick with recessed black mortar joints. Bricks of normal shape were used in the construction of the tower and these have provided a lively pattern of light and shade, particularly within the stair well throughout its height.

The local authority at first demanded stucco facing or London stock bricks rubbed with ‘soot’ for this house. The present dull, rugged, dramatic surface is a rebuke to all such suggestions for evasions of honesty in purpose.

Blue-black brick paviors and quarry tiles laid on concrete have been used for floors, and this has given the house an unusual unity, seen at its most exciting in the living-room and in the kitchen where the white Formica doors of the Hygena fitments form a gleaming contrast with the tiles.

The architect has incorporated a number of unusual practical devices throughout the house, any one of which would merit the attention of firms marketing well-designed fitments. The light fittings, for example, are in precast concrete and used externally and internally, built into the brickwork. They are inexpensive, ingenious and imaginative and provide a pleasingly diffused light when inset upturned into brickwork, a direct light when used down-turned. In the spare room, the upper of the two single beds pivots to become a working-table, a very useful device which could well be adapted for use in students’ hostels.

But this house abounds in novel features, externally and internally, and despite the fears of the neighbours and an initial tendency towards a ‘Down with Bailey’ movement, the house has now settled amongst its brick and stucco neighbours as little more than one esoteric element in a street of wayward charm and individual fancy.